Explained

Fugues

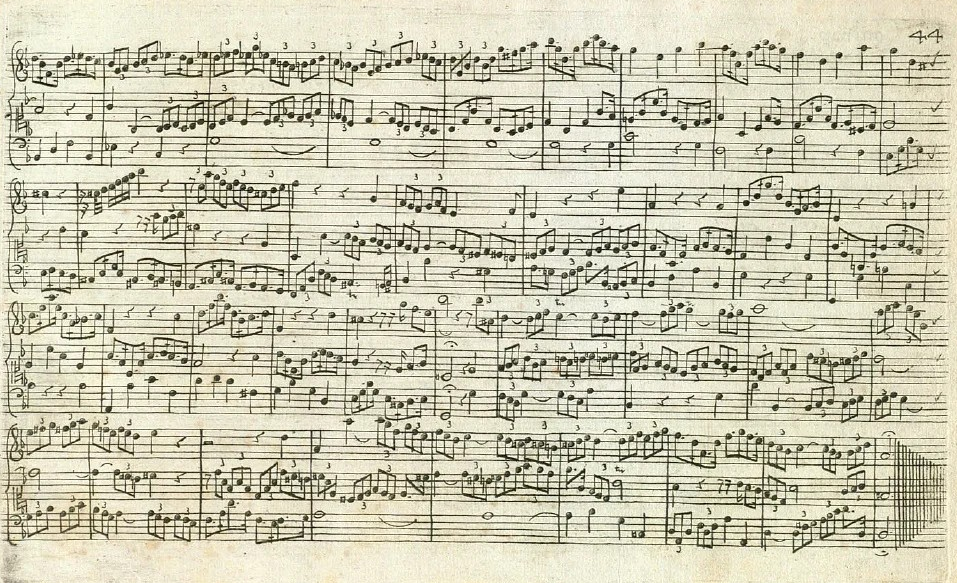

The fugue, a contrapuntal composition in which multiple independent melodic lines are woven together, has fascinated composers and listeners for centuries. Its early beginnings can be traced to the late Renaissance, where it evolved from the imitative counterpoint of composers like Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. By the Baroque era (1600–1750), the fugue had matured into a sophisticated art form, reaching its zenith in complexity and popularity.

This form, based on the idea of imitation, follows a clear structure. It starts with the exposition, where a single melody, the subject, is played by one voice alone. Then, other voices enter, each playing the subject, often at different pitches, creating a woven pattern of melodies. This imitative entry, usually following a pattern of tonic and dominant relationships, sets up the fugue’s main theme. A key part of the fugue's detailed design is the countersubject, a second melody that often plays with the subject, adding more layers of contrapuntal complexity.

After the exposition, the piece moves through episodes, transitional parts that often use pieces of the subject or countersubjects, providing moments of harmonic and melodic contrast. These episodes help change keys and prepare for later entries of the subject.

The development sections of a fugue show the composer’s skill, where the subject is changed through techniques like stretto (overlapping entries of the subject), augmentation (making the notes longer), and diminution (making the notes shorter).

Finally, the fugue often ends with a final statement of the subject, sometimes in stretto, bringing the piece to a satisfying and structurally complete finish. This careful arrangement of melodies, combined with rich harmony and contrapuntal skill, makes the fugue a testament to the composer’s intellectual and artistic skill.

Explained

Types of Fugue

The fugue, while unified by its core principles of subject, exposition, and contrapuntal development, manifests in diverse forms, each bearing its own unique character.

The strict fugue, adhering rigorously to the subject's presentation and development, showcases the composer's mastery of canonical imitation and unyielding adherence to form.

Conversely, the free fugue allows for greater latitude, incorporating episodes of more improvisatory nature and permitting deviations from the subject's original contour.

The permutation fugue, a variant often encountered in Baroque organ works, features the subject in a series of transformations, such as inversion or augmentation, creating a kaleidoscopic interplay of melodic shapes.

The double fugue, a testament to contrapuntal complexity, introduces two distinct subjects, which are developed and interwoven, culminating in their simultaneous presentation.

Finally, the counter-fugue, or fuga al rovescio, presents the subject in inverted form, challenging the listener's ear with its altered melodic direction, thereby revealing the profound versatility inherent within this venerable musical structure.